The Last Single-Family House in the Murphy Addition

The first of Nashville’s turn-of-the-century streetcar suburbs is lost to history. but one home tells its story.

This is an extended version of an article that appeared in the Nashville Scene. Read that version here.

This piece is a companion to The Loneliest Little House in Nashville, which highlights the Watkins Park neighborhood adjacent to the Murphy Addition and covers complementary themes of Nashville’s first zoning ordinance.

Photo credit: Eric England, The Nashville Scene

This article is a 40- to 50-minute read.

Want the basics before diving into the details? Explore the article with NotebookLM or listen below:

Twenty-First Avenue North is no place for a house.

Three lanes of one-way traffic facilitate quick cut-throughs from Charlotte Avenue to Church Street, West End Avenue, and the eastern gateway of the Vanderbilt University campus. The surrounding blocks are no better—ambulance sirens are the neighborhood soundtrack, with two major hospitals anchoring opposite corners of the district. The hospitals have drawn a smattering of subservient medical offices, with surface parking lots that offer convenient access but create a visual blight and make the summer sun scorch hotter.

One could be forgiven of disbelief that this district was once, for a fleeting moment, the finest residential section in Nashville—only scarce few hints remain. One sits at 321 21st Avenue North, but it too requires a sort of architectural x-ray vision to see its former splendor through the patina. Its green roof shingles have not been fashionable in decades, and years of weather have nearly turned them black. Air conditioner units pop out of each window to a front porch defined by thick doric columns atop stone pedestals, holding up the old roof and its Craftsman exposed eaves.

The house is the only building on the block that greets the sidewalk. The parking lot of a dental office aligns with the house on its north side, while a fenced lot for outdoor storage sits to the south and the concrete skeleton of a multi-story medical office building rises in the background. The old style of the house stands out among the many muted mid-century modern medical office buildings and the antiseptic architectural language of their contemporary counterparts. It is not the only old house in the district—there are a handful strewn about, often grander and with more exquisite brick facades—but 321 21st Avenue North is the only one that has not been converted into professional offices or some other modern use.

It is the Last Single-Family House in the Murphy Addition, and its days are numbered. This is no place for a house.

The Electric Rise of Streetcar Suburbs.

The Murphy Addition was the first of Nashville's grand, turn-of-the-century streetcar suburbs. While predecessors like Germantown, Edgefield, and Belmont had pioneered the streetcar suburban model, the Murphy Addition refined it. The sixty-six-acre spread was the first to be subdivided in conjunction with a streetcar line owned by the same developer, with its lots sold off in an entire section. In 1902, the Murphy Land Company entered into an agreement with the city to build a complete suite of infrastructure—streets, sidewalks, curbs, gutters, water and gas mains, and a sewer line—through the section ahead of its development at a cost of more than $10 million in 2025 dollars; earlier developments funded these improvements privately or waited for the city to extend services as the lots were sold.

By 1904, the section was selling lots at a pace of seventy per month, aided by financial innovation—buyers could put 25% down and pay the balance in monthly installments over ten years at five percent interest. (Doyle, p95) Lot sales were consummated on conditions “intended to prevent the property from being made undesirable as a place of residence.” Purchasers were deed restricted from using the property for businesses, a house less than twice the cost of the lot, or for the use of “any person or persons of African blood or descent.”

The restrictions were central to the marketing strategy and positioning of the subdivision—not merely a legal formality.

Full-page advertisement in the Nashville American | June 4, 1905

A full-page ad in the Nashville American touted the “high class restrictions” in the Murphy Addition and reminded prospective buyers: “Don’t forget that the value of real estate is determined by the restrictions placed on it and the character of improvements that surround it.” Racially-restrictive covenants and their relentless promotion were the great local innovation of the Murphy Land Company, which its competitors soon adopted across Nashville—most prolifically, the Bransford Realty Company which subdivided or sold lots in Richland, Belle Meade, Belle Meade Golf Links in the 1900s.

The Murphy Addition successfully drew many of Nashville's civic and business elite, as it was “not only a pleasant site for a home, but a safe and sensible investment of their money.” The neighborhood boasted distinguished lawyers, judges, and women's suffrage activist Anne Dallas Dudley.

The Murphy Addition had quickly become known as the finest residential section in the fast-expanding city, but its exclusivity would not last long. The strategies employed by the Murphy Land Company—comprehensive development of a complete tract by a well-capitalized development syndicate, coordinated with a company-owned electric streetcar line, supported by city investment in infrastructure, and protected with deed restrictions—were adopted and improved upon by competitors whose subdivisions soon surpassed the Murphy Addition.

Richland and Belle Meade were both subdivided by 1910, each pulling elites further out from the city center in a relentless westward trend. Meanwhile, middle- and working-class subdivisions in West Nashville carried lower classes on the streetcar lines through the Murphy Addition. One resident complained of “the crowding of the tobacco smokers, chewers, negroes and pickpockets on the rear platform of the cars.”

By the 1920s, the Murphy Addition was a solidly second-fiddle subdivision—a few small apartment buildings soon sprang up, scattered throughout the section, and many classified ads offered duplex units for rent. As the decade came to a close, although still populated by a number of prominent citizens, it had grown clear that the exclusivity of the Murphy Addition suffered from the dynamism of an unrestrained real estate market and an inability to control surrounding developments.

Super-Slums, Disease, and Moral Reform.

1907 editorial cartoon from The Nashville Banner depicting a white woman with a smear—labeled Black Bottom—upon her cheek. "A horrid blemish—cannot the city council concoct the lotion to remove it?"

The drive for suburbanization among Nashville's upper classes had existed for decades prior to the subdivision of the Murphy Addition. After the Civil War, Black people newly freed from enslavement on the farms and plantations of Middle Tennessee streamed into the city for work and a comparatively more liberal social atmosphere. Most found their gateway to the city in the slums that developed around railroad tracks and low-lying, flood-prone areas of the city center populated also by Irish immigrant rail- and dockworkers. The poor physical conditions of the slums were breeding grounds for disease—cholera and tuberculosis outbreaks were frequent and devastating. Elite whites decamped to Edgefield and other early suburbs, protected from the lower classes by the prohibitive cost of transportation with access only by private means or rudimentary, mule-drawn streetcars.

As the Irish assimilated and ascended to the middle class, the slums and their problems grew increasingly racialized. Though Blacks and whites had lived side-by-side in Nashville for a century, the conditions of the slums became associated with Blackness itself. The city’s health department in 1899 reported that disease and “the high death rate among the colored people is due to... improvidence, ignorance, lamentable neglect of personal cleanliness... and above all, the negro has to contend with this marked racial susceptibility to all forms of tubercular disease.”

The deterioration of inner-city slums coincided with a religious revival movement that infused moral reformers with the zeal of converts. The source of all sorts of vice, intemperance, disease, and destitution was ascribed to the Black population. Civic and humanitarian associations were formed to ameliorate slum conditions, often with a combination of paternalism and resentment best represented by Nashville's halting attempts at local prohibition and retaliatory voting restrictions. (Doyle) Police cracked down on vice in slum areas like Black Bottom, disproportionately arresting Blacks at the behest of “City Beautiful advocates anxious to clean up the area [and] white property owners fretting about depressed land values.” (Houston, p25)

The fight to rectify the moral conditions of Black Bottom was deeply entwined with racial segregation and containment of the expansion of Black districts. The first flashpoint was a proposed industrial education academy for Black girls, to be located on Seventh Avenue South:

“To the affluent white residents of the area, a black school threatened to crack the invisible to implacable wall separating their neighborhood from Nashville’s black and poor, who ebbed and flowed around it...

In the minds of many white South Nashvillians, a Negro academy on Seventh Avenue would encourage the black resurgence. Through the tiny opening in the dike, ran the course of their nightmare, a few blacks would trickle onto the streets near the school. Then gradually a Negro tide would inundate the area.

The imaginary prospect caused the relocation of a few long-time residents. Others tried frantically to thwart the nuns’ plans, seeking to have the proposed site - an imposing mansion - demolished, based on a clause in an early dedication of the street fronting the property. They also applied their influence at the city hall and the county courthouse. Given the dire possibilities that the new school would open, they told officials, it was no longer enough to try to hold the growth of Negro neighborhoods in bounds. If South Nashville were to be preserved, a chief source of pressure, Black Bottom, would have to be removed.”

In the final days of 1906, Mayor T.O. Morris ordered police to crack down on loitering, indigents, brothels and love hotels, and “certain dance halls, etc., where men and women of both races congregate.” An ordinance barred the retail sale of liquor south of Broad Street—according to Summerville, “primarily aimed at Black Bottom… By halting the sale of alcoholic beverages there, city officials pleased the coalition calling for the district’s outright destruction, placated the powerful anti-liquor forces, and caused several prime commercial locations in the Bottom to fall vacant. As city leaders knew, the owners of these properties would be amenable to offers of purchase from the businessmen across Broad who were avid for expansion.”

While harsh policing controlled the social atmosphere of the slums, like hand in glove, moral reformers targeted the physical environment. Public works projects as a means of slum clearance, which would define the middle half of the 20th Century, were prototyped in the early 1900s. The South Nashville Women's Federation—one of the civic associations established by moral reformers—pushed a bond issue to “clear Black Bottom” with the construction of a public park and a bridge over the Cumberland.

Clearance of Black Bottom was a cause for elites of both races—but while white appeals against the slum attributed its conditions to Black inferiority, leaders in the Black community saw an opportunity to dispel racist notions and break the link between Blackness and immorality. The Nashville Globe, the leading Black newspaper, ran an editorial by prominent Black leaders on November 10, 1910, urging the passage of the park bond:

“The Negro citizens are especially solicitous that the white people of this county continue to give their support in the moral uplift of the race. They believe that the elimination of Black Bottom will remove great evils, crimes, temptations and a spot from the city that breeds crime and criminals... The vote that you give at this election... will be a personal favor to the Negroes of this county as well as a duty you owe to see to it that our city is made more beautiful, pure and less sinful.”

There is a notable contrast between white notions of immorality, disease, and vice—as problems to which Black people were predisposed, deserving of punishment, and transferred to otherwise morally pure whites through interracial contact—and the Black framing of slum problems as an affliction forced upon a population with potential for uplift.

But the white perspective won out. Though the bridge was built, the park failed “in part because of fears that slum dwellers would only migrate to middle-class neighborhoods.” (Doyle, p82)

While reformers fought—often in vain, and often with a cynical paternalism—against the problems of the city slums, the streetcar suburbs emerged as a flight response. Their essential purpose was deeply linked with racist ideas of public health and morality—the Murphy Addition was advertised as a “suburban park” with “pure air” free from the “disease and vice” of the city. Its deed restrictions sought to attract “desirable purchasers only” with a ban on Black residence enumerated immediately after a restriction against the “charitable institution[s]” established by moral reformers to heal the diseased slums and just before a ban on swine and other uncleanly farm animals.

In the turn-of-the-century suburbs of other metropolitan areas, the connections between Black residence, disease, and property value were more explicitly drawn in deed restrictions. The Edgemoor subdivision in Bethesda, Maryland included deed restrictions with the following language:

“That whereas the death rate of persons of African descent is much greater than the death rate of persons of the white race and effects injuriously the health of the town and village communities and as the permanent location of persons of African descent in such places as owners or tenants, constitute an irreparable injury to the value and usefulness of real estate, in the interest of public health and to prevent irreparable injury to the grantor or its successors or assigns, and the owners of adjacent real estate, the grantee his heirs and assigns hereby covenants and agrees with the grantor, its successors and assigns, that he will not sell convey or rent the premises hereby conveyed, the whole or any part thereof, or any structure thereon, to any person of African descent”

Similar deed language was used widely throughout the Washington, D.C. suburbs and other border state urbanizations. The elaborate exposition for a restriction that spanned a single sentence in Nashville was not merely an artifact of the verbosity of overeducated Yankees, but rather a legalistic effort to insulate the racist covenants from threats by a burgeoning civil rights movement. By drawing disease directly into the justification for exclusion of Black residents, the deed restrictions could be more ably defended as within a local government’s police power to promote public health. By supposing the fact that Black residence causes the destruction of property values, the restrictions could be defended as private protection against malicious injury to white property owners—a line of argument judges of the era often found sympathetic.

In Nashville and other cities further south, the connection between Black residence, disease, and property value decline was so obvious that it needed no exposition—and the legal precedents of Jim Crow laws, segregation of public spaces, economic oppression, disparate policing, and unequal justice were so strong as to obviate the need before the courts and their subjects, alike. Above all, racist restrictive covenants reflected the conventional wisdom of the white elite, formalized as a contract, in the shadow of seemingly futile slum reform efforts.

With their mistaken premises, moral reformers failed to solve the problems of the slums. The civic and social elite of genteel Nashville fled to suburban subdivisions insulated from the slums by a web of private regulation and social custom. A sibling project of the civic elite—business progressivism—would soon develop a more enduring alternative through use of the police power to zone and regulate land uses.

A National Language with Local Dialect.

The overall failure of early moral reformers, City Beautiful advocates, and civic leagues to eradicate the slums was not entirely without successes. Reformers also made genuine physical improvements to combat slum conditions—even as they dovetailed with Jim Crow laws, the religious fervor of moral reform, and a broader segregationist trend.

A sewer system was laid, though most families couldn’t afford to hook up to it. While critical to the reduction of disease, the uneven distribution of sewers contributed to segregation (Trounstine) through a sorting effect. Upper class white Nashvillians could afford to purchase property boosted in value by the presence of sewers, like in the Murphy Addition. Meanwhile, Blacks and immigrants piled into the unsewered slums—where the City Hall political machine “sent municipal workers and quantities of pipes… on election eve, creating anticipation that new sewers would be laid—with a quick overnight withdrawal of the workers and materials after the election” in cynical ploys for electoral support. (Houston, p31) With sewer expansion racialized and out of reach of the lower classes, the Black death rate from disease remained double that of whites well into the 20th Century.

While the effect of sewer infrastructure on Nashville’s slum conditions was somewhere between marginal and manipulative, reformers found greater success above ground. A building code was implemented in 1909 and expanded into a 236-page document declared “the best in the United States” by 1916. The Great East Nashville Fire, which swept through Edgefield just months before the expanded building code was adopted, would be the last massive conflagration in the city. Many of the health and safety regulations that would later be adopted into zoning ordinances were already in place in Nashville with the 1916 building code and more stringent fire rules adopted the following year:

“The ordinance also required houses to be constructed a minimum distance from the edge of the street and prohibited new buildings from covering more than a specified portion of a lot. New houses were required to meet lighting and ventilation standards. Other construction standards were strengthened and the scope of regulations broadened.”

Other aspects of the 1916 building code were valued in other sections of the city. The South Nashville Improvement Club—the businessmen’s version of the South Nashville Women’s Federation, which was organized in 1914 to push back against residential decline and the expansionary pressure of Black Bottom—looked on approvingly:

“An important effect of the establishment of the new fire district will be to bar certain elements from sections of the city where they are not wished. Very poor people will be unable to live in houses that come up to the requirements of the fire district, and will consequently be barred from its limits. The South Nashville Improvement League is taking an especial interest in this feature of the proposed laws.”

These efforts built the coalition for city zoning—joined by Nashville real estate interests, the chamber of commerce, and suburban homeowners—with heavy promotion as early as 1911 and continuing throughout the decade. A movement in its infancy, the vision for comprehensive city planning was initially divided between factions which advocated for different means, even as their ends overlapped. On one side were the moral reformers, public officials, and City Beautiful veterans who pushed to clear the slums and revitalize the inner city with a project of grand boulevards, civic centers, and parks. On the other side, the rise of streetcar suburbs led to a consolidation and professionalization of the real estate industry, which sought to improve the marketability of suburban developments by ensuring the endurance of property values.

It was the vision of the latter which would come to dominate the development of city planning and zoning—both nationally, as detailed extensively by historian David M.P. Freund in Colored Property, and locally:

“The time was when we, as proprietors of small tracts platted and marketed without restrictions on their development, for fear we might by restrictions scare off buyers who would not have us limit their liberty or license to do as they pleased with their property. But now we have learned that wise restrictions are for the benefit of all—larger profits to the proprietor, greater value and permanent protection to the purchaser, and more attractiveness and lower cost of operation to the city...

Let us... take the advanced stand, applying the knowledge we have of the benefits of restrictions in our additions to the city as a whole and join in the movement for intelligent city planning. The city as the larger proprietor can plan and restrict the whole city’s development with the same advantages that we as smaller proprietors obtain in restricting our plats...”

Under the influence of real estate interests and proponents of “scientific planning” like Edward Bassett, Lawrence Veiller, and Harland Bartholomew, the movement for city planning and zoning grew intensely focused on the “prevention of economic waste” caused by intrusion of commercial and industrial uses and “inharmonious racial groups” which drove “well-to-do families” out of “finer residential districts.” Bartholomew noted that “entire residence districts have been deserted by all but the poorest class of tenants when invaded by scattered business and industrial establishments” while real estate developers and homeowners could ward off such invasions only for the limited period of time set forth in restrictive covenants.

The movement of fashionable residential areas around the city and the filtering of houses down to lower classes of occupants—later known as economic waste—was a well established trend locally, as documented in Shifting Residential Patterns of Nashville. The city had started around Public Square, with shopkeepers living above their businesses, but “as less desirable businesses moved into the area, the families sought residences elsewhere.” A mansion district on Vine Street transitioned into boarding houses, as new generations were unable to maintain or modernize the expansive homes. While the article declares that “an entering wedge would be made through the sale of one residence, and eventually the entire block would fall,” it goes on to note soon thereafter that one such mansion-to-boarding house conversion “sold as business property for $30,000 the first time, and at the last resale it went for $200,000.”

Accurate accounts of these processes can be difficult to attain, as histories like Shifting Residential Patterns are often sympathetic to upper class sentiments and imbued with the biases of their age—such as its only reference to apartment houses, described as containing “people compartmentalized as are eggs in a carton.” A more sober review of the commercialization processes of exclusive residential districts can be found in Growing Metropolis: Aspects of Development in Nashville, which characterizes the transition of mansions to boarding houses as a natural, intermediary step toward more intensive urban development in response to household economics, demand shifts toward suburban housing, and rising commercial land values. This view is supported by a 1904 newspaper article extolling the “excellence of the new Murphy Addition” which attributed its demand to “those owning homes in the more central parts of the city, who, because of the increasing demands for store sites, were rapidly being induced to give up their residences in those quarters.”

As these trends continued to roil the fine residential districts of American cities over the following decades, each explanation amalgamated into a collected wisdom. A 1939 Federal Housing Administration report, entitled The Structure and Growth of Residential Neighborhoods in American Cities, describes the down-filtering process as an inevitability internalized to the peculiarities of the mansion, itself, but hastened by the intrusion of other racial groups:

“Both the buildings and the people are always growing older. Physical depreciation of structures and the aging of families constantly are lessening the vital powers of the neighborhood. Children grow up and move away. Houses with increasing age are faced with higher repair bills. This steady process of deterioration is hastened by obsolescence; a new and more modern type of structure relegates these structures to the second rank. The older residents do not fight so strenuously to keep out inharmonious forces. A lower income class succeeds the original occupants. Owner occupancy declines as the first owners sell out or move away or lose their homes by foreclosure...

These internal changes due to depreciation and obsolescence in themselves cause shifts in the locations of neighborhoods. When, in addition, there is poured into the center of the urban organism a stream of immigrants or members of other racial groups, these forces also cause dislocations in the existing neighborhood pattern...

The highest grade neighborhood, occupied by the mansions of the rich, is subject to an extraordinary rate of obsolescence. The large scale house, modeled after the feudal castle or a palace, has lost favor even with the rich. When the wealthy residents seek new locations, there is no class of a slightly lower income which will buy the huge structures because no one but wealthy persons can afford to furnish and maintain them. There is no class filtering up to occupy them for single-family use. Consequently, they can only be converted into boarding houses, offices, clubs, or light industrial plants, for which they were not designed. Their attraction of these types of uses causes a deterioration of the neighborhood and a further decline in value. These mansions frequently become white elephants...”

While there is scant evidence that commercialization alone harmed property values, there is a prolific historical record of residential abandonment as a response to racial intrusion—later known as white flight—which often followed commercialization. Restrictive covenants—first applied exclusively in high-class residential districts like the Murphy Addition—were a response to these processes and the inherent vulnerabilities of the single-family mansion house.

Before the professionalization of the real estate business and the implementation of protective tools like restrictive covenants, Nashville property owners had limited options to forestall transitions in land use and racial makeup. According to Shifting Residential Patterns:

“Between Broad Street and Howard Street sprawled Black Bottom, a Negro section where cheap rent on cheaper property made it an exceedingly profitable investment for real estate dealers... Those who lived in the area beyond Black Bottom made some effort to halt the inevitable. Oliver Timothy, a merchant who lived on South College Street (Third) kept Negroes away from Howard School by buying forty houses and controlling the rental of them.”

Those who remained in areas like South Nashville, pressured by Black Bottom, formed neighborhood improvement associations to beautify properties, lobby for public infrastructure, protest “Negro churches” in white neighborhoods, and oppose the construction of “Negro apartment” buildings.

At a 1917 meeting of the South Nashville Improvement Association—in which Oliver Timothy gave the opening remarks—Dr. Paul Harvill, the president of the Big Brothers, “[spoke] of how some undesirable neighbors had been kept out of certain South Nashville sections… [and] announced that if any man in South Nashville wanted to improve his home, the South Nashville Improvement Association would loan him the money.”

Another attendee spoke optimistically about a case before the U.S. Supreme Court: “We believe that in the event certain legislation proves to be constitutional, South Nashville will more than any other section gain a new impetus.”

Of course, even the select few who had the resources to buy up large swaths of the city as a firewall against racial “invasion” rarely considered it a worthy investment. Already by the turn of the 20th Century, local elites found it much easier—and cheaper—to simply move to the latest and greatest streetcar suburb. But as low-cost electric streetcar lines made new suburbs accessible to the middle class, a growing pool of homebuyers and builders sought a more permanent solution to the problem of racial invasion, white flight, and the “economic waste” that followed.

From Racist to Racially Informed.

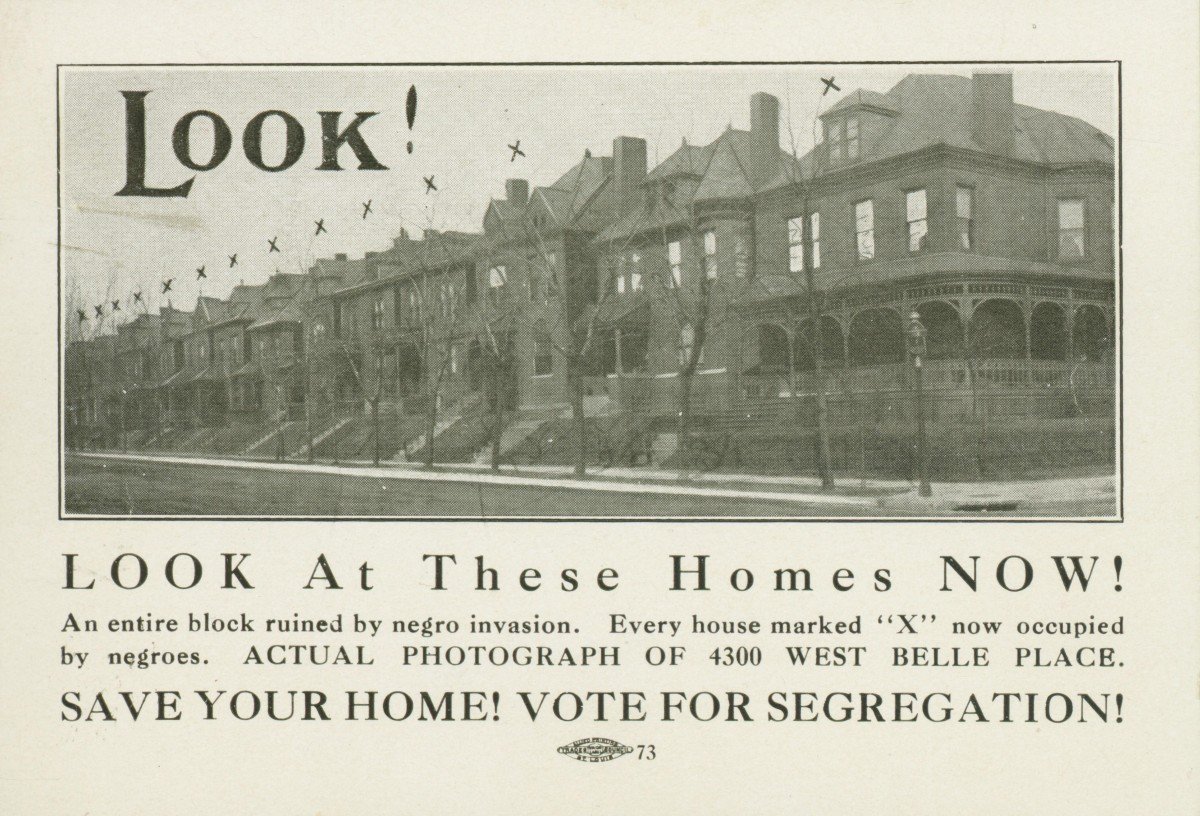

Pamphlet advocating for the 1916 racial zoning ordinance in St. Louis, Missouri | Source: The Making of Ferguson: Public Policies at the Root of its Troubles by Richard Rothstein

The city planning and zoning movement drew on a racialized view of property markets disseminated by national real estate and city planning organizations and typified by local attitudes toward the occupants of slums like Black Bottom. The idea that racial intermixture constituted an inherent threat to property values in white neighborhoods—referred to variably as the market imperative or racial theory of property value—formed the earliest impetus for citywide zoning laws in the United States.

In 1910, Baltimore enacted an ordinance that prohibited residents from purchasing property on a block more than 50% occupied by the opposite race. Mayor J. Barry Mahool supported the law by stating that “Blacks should be quarantined in isolated slums in order to reduce the incidents of civil disturbance, to prevent the spread of communicable disease into the nearby white neighborhoods, and to protect property values among the white majority.”

At least twenty-seven cities—primarily in the South and border states—passed similar laws from 1910 to 1917. Nashville was not among those cities.

Scholars have identified a connection between the adoption of racial zoning ordinances and the rapid growth of Black populations, drawn to cities like Louisville, Birmingham, and Richmond by industrialization of local economies. Nashville never industrialized to the extent of other regional peers, and its Black population declined in the 1910s. That Nashville never joined the ignominious list may have been a simple coincidence, as the only decade of Black population loss in the city from the Civil War to the present day occurred during the short window of racial zoning.

If Nashville’s Black population had grown more rapidly during the 1910s, pressuring more white neighborhoods, perhaps other sections of the city would have joined the South Nashville Improvement Association:

“An important feature of the [July 7, 1914] meeting was the appointment of a committee with power to act in influencing city commissioners to pass an ordinance providing for a separation of the negro and white races in residence sections. The committee was directed to endeavor to secure the passage of an act similar to ones now in force in Louisville and Baltimore, and being agitated in Birmingham. The preamble to the Louisville ordinance reads: ‘An ordinance to prevent conflict and ill feeling between the white and colored races in Louisville and to preserve the public peace and promote general welfare by making unreasonable provisions requiring as far as practicable the use of separate blocks for residences, places of abode and assembly by the white and colored people respectively.’

C.A. Brenglman, Oliver J. Timothy and James T. Camp compose the committee appointed.”

The improvement association, which was founded two months prior “out of the need of the elimination of unsightly spots and undesirable characters” in the district, sought “co-operation of all the business organizations of the city… to render their influence in the passage of the ordinance providing for the separation of the negro and white races in residence sections.”

The U.S. Supreme Court declared racial zoning unconstitutional in the landmark 1917 decision, Buchanan v. Warley. The South Nashville Improvement Association fizzled out by 1920.

Several cities passed racial zoning ordinances after the Buchanan decision, either in defiance or to test the limits of jurisprudence. Other cities, like Atlanta in 1922, simply re-coded their racial zones with different nomenclature, without changing any of the underlying standards. None of these attempts survived court challenges, given the clear and recent precedent set by the Supreme Court.

But while the Buchanan decision invalidated racial zoning ordinances, it did not defeat the logic of residential segregation. In fact, some scholars argue that the basis of the decision—that racial zoning ordinances were unconstitutional infringements upon the rights of white property owners to transact freely—served to bolster the market imperative defense of zoning as a means to covertly segregate by race.

Racial zoning, rather than being banished to a shameful chapter of history, simply evolved into “racially informed” zoning. Historian Christopher Silver notes, “The Buchanan decision undermined the use of zoning to segregate explicitly by race but not the use of the planning process in the service of apartheid.” Racial segregation was codified by proxy in zoning laws through methods pioneered by city planners like Harland Bartholomew, who became the first full-time planner in the country when he was hired by St. Louis in 1916—the same year the city passed a racial segregation ordinance designed to stop “Negro invasion” into white residential neighborhoods.

Harland Bartholomew & Associates, which had rapidly grown into the leading planning consultancy in the country by the 1920s, developed comprehensive plans for dozens of cities using the same methods he employed in St. Louis shortly after the Warley decision. His firm surveyed and mapped cities block-by-block, with close attention to the types and uses of buildings, blighted and depreciated properties, and race of occupants. Zoning categories were then drawn to segregate commercial and industrial uses from higher-class residential areas, which were segmented from other residential zones with more restrictive standards. Areas with “blighted and depreciated” housing—almost exclusively Black or mixed-race—nearby “fine residential areas” were often assigned commercial or industrial categories to encourage redevelopment, as were low-lying areas where racialized topographies had emerged. Master street plans drew major thoroughfares along the lines of different zoning classes to harden the borders of districts with different characters.

The faults in Bartholomew’s pseudoscientific methods and economic orientation are set in stark relief by his analysis of the slums, which was loaded with racialized assumptions. In his 1932 assessment of The Negro Housing Problem in Louisville, which included a detailed Survey of Negro Housing Conditions, he notes: “Slums are present in some form or another in every municipality, and their existence is a direct challenge to those who seek to better the social and economic status of the city. The effects of bad housing on the health and morals of the community are too well known to enlarge in this study…” But despite identifying substandard housing as a causal factor in slum problems, Bartholomew nonetheless concluded: “If it were possible to create among the Negro masses a real desire for decent accommodations, the slums would automatically eliminate themselves as it would be impossible for the owner of rundown property to attract them.” Unable to imagine Black agency—or interrogate, rather than merely describe, the conditions that stood in the way—Bartholomew instead arrived at the conclusion that “some form of large-scale slum clearance and rehabilitation is the only real cure.”

Harland Bartholomew & Associates completed work in cities surrounding Nashville—from Memphis to Chattanooga to Louisville—and cast the die for planning practices based on a “scientific” method both informed and muddled by unscientific biases about race. City planning and zoning in Nashville would form to the mold set by HB&A.

Boss Howse Versus the Business Progressives.

The infiltration of property interests as the driving force of the city planning and zoning movement—expressed by the market imperative narrative for segregation and Bartholomew’s emphasis on economic waste—was part of a broader movement in which businessmen grew more active in the civic sphere. Business progressives from Nashville to New York City saw city planning and zoning as a means to isolate city-building work from the political whims of machine politics—and secure it under their own control. As noted in The Advent of Zoning by Garrett Power in 1989, “New York and other cities were controlled by political machines which catered to working class elements. Zoning and other municipal reforms were designed to shift control to the upper classes.”

A Nashville city planning and zoning commission was pushed through state and local legislatures by the Chamber of Commerce—first enabled by state private act in 1925 and then created by a city charter amendment the same year. But the commission was resisted by Mayor Hilary Howse, a machine politician who owed his power to patronage and working-class voters in the inner city. While Boss Howse stalled, the business elite launched a public campaign. The Nashville Tennessean, owned by prominent businessman Luke Lea, ran a series of editorials promoting the potential for city planning to usher in an era “dominated by the best and most intelligent thought of the community and not... subservient to any political or factional interests.” The subtext: a machine boss mayor held too much power and doled out riches to undeserving Black and inner-city poor populations in exchange for votes.

Another Nashville Tennessean editorial, from 1928, reinforced the practical, market imperative case for zoning:

“City zoning and a proper scheme for city development will prevent the tragedy of property value declines through shifting and changing populations. There is nothing more tragic in the field of purely material things than the destruction of vested property values through the deterioration of a neighborhood... Property that was once highly desirable and eagerly sought will no longer bring the cost of its buildings. Due sometimes to the invasion of a section by some interests that makes it undesirable for homes the population is scattered and a formerly most desirable neighborhood loses all of its attractions. It is the purpose of those who advocate zoning bills to make a situation of this kind virtually impossible.”

This concern about property value declines as a result of “shifting and changing populations” was made more explicit in an influential 1930 report by YMCA Graduate School professor J. Paul McConnell titled Population Problems in Nashville, Tennessee. In the report, McConnell wrote:

“As a whole, these sections of bi-racial residence, are very undesirable and unwholesome, due to low property valuation, low rentals, no repairs on residences, poor streets, drainage and sewerage systems, serious over-crowding and numerous racial contacts... The marked residential intermixture of two major races constitutes a serious problem for our social welfare agencies as well as for the city health department, park commission, school board, and police department.”

It was these two strains that formed the basis of the argument for city zoning in Nashville:

The impact of footloose populations and overly dynamic real estate markets on heavily invested homeowners and businessmen

The impact on “good governance” wrought by the mixed neighborhoods left behind by cycles of elite flight to new, segregated suburbs

Amidst a bevy of political attacks and charges of corruption, Howse sought to assuage his enemies in the civic elite—most prominently, Luke Lea and his Nashville Tennessean—by relenting to reforms promoted by business progressives. Howse finally appointed a City Planning and Zoning Commission in 1931, with four of its five members businessmen tied into the Chamber of Commerce. The commission soon hired a young urban planner named Gerald Gimre and set out to study the land use patterns of the city.

A native of Iowa who came to Nashville by way of planning stints in small Ohio cities, Gimre was described by Rachel Martin in Hot, Hot Chicken as having "one of those Midwestern faces that was remarkable only because it was so everyday handsome… but without any charisma to draw his viewer. He looked competent and prepared and forgettable.”

And that is how Gerald Gimre was as a planner—competent, prepared, and forgettable.

Unlike Harland Bartholomew and a few future Nashville planners, Gimre was never a thought leader in the field. He was a skilled implementer of the ideas of others, including Bartholomew’s methods for “scientific” analysis and planning of the city, and he was an eager executor of federal programs. Gimre’s DNA as a planner was the genetic code of the national planning movement transcribed onto a local context increasingly dominated by business interests.

Planning for the Present.

Nashville’s nascent Planning and Zoning Commission approved a rudimentary zoning ordinance in 1932 to stand in until the completion of Gimre’s land use study could inform a proposal for a permanent zoning ordinance. The temporary ordinance was lean and oriented toward maintenance of present conditions. Zoning classification was determined by the existing use of the property and prevented businesses or apartments from being built in areas that were more than 80% single-family residential—almost exclusively new, all-white suburban additions, often with segregation reinforced by private covenants.

The city planning and zoning commission heard nine appeals under the temporary ordinance, each a petition to open a business in a residential zone. One case involved a proposal to move a filling station at 1400 Fatherland Street across the street to 1401 Fatherland, which was approved without protest. Another East Nashville case rejected a request for a temporary structure at the corner of 20th and Boscobel (adjacent to Shelby Park) to sell refreshments during the summer months, as a neighbor protested that it would hurt the value of her property at the opposite end of the block. Permission to construct a dry cleaning plant—in a residential section where Vanderbilt University Medical Center now stands—was rejected upon the protest of neighbors. A filling station at 44th & Charlotte Avenue was approved, despite its Residence A District location, in the absence of protests from neighbors.

A more controversial petition to build a filling station and grocery store buildings along West End Avenue in the Richland Addition drew a petition of opposition signed by 40 neighboring homeowners, along with a handful of speakers, many of whom cited the deed restrictions against commercial property—and Black occupancy—which were set to expire at the end of the year. One of the speakers was the vice president of the Richland Realty Company, the development syndicate which subdivided the Richland Addition, who protested that the filling station would “depreciate the value of the residences in one of the best residential sections in the city.”

The proposal was rejected, reheard, and rejected again—the second time with the protest of 276 residents of the Richland Addition noted. The decision of the commission cited the location in a Residence A District, “in a large and populous area where the lots were sold under building restrictions which will expire on January 1, 1933... that there is no necessity nor demand by the residents for business houses at said location, that the erection of business houses and a filling station... would depreciate the value of the residences heretofore erected in Richland Addition... [and] that the decision... in refusing permit... [is] hereby approved and affirmed.”

The themes of these cases would reoccur “in the months and years to come,” according to Robert James Parks in his 1971 Vanderbilt University thesis Grasping at the Coattails of Progress. Parks identified three key characteristics of the cases brought to appeal the temporary zoning ordinance:

“First, they involved the desire of someone to construct a business building or convert an existing building to a business use in a residential zone.

Second, the board’s decision in many cases was strongly influenced by the extent of citizen objection. If no one objected, generally (but certainly not always), the appeal would be granted. If several objected (but again not always), the appeal would usually be denied.

Third, the arguments for and against appeals often centered on the effect of the proposed change upon neighborhood property values. Only rarely did the argument center around the best use for a particular parcel of property in relation to surrounding uses, the street pattern, traffic movements, and the long-range development of the neighborhood.”

Before Nashville had even adopted a permanent zoning code, its planning system had conformed to an exasperated analysis by “The Father of Zoning” Edward Bassett in 1925: “It is remarkable to what extent the zoning plan becomes what the property owners of each district want it to be. Arguments about what will be for the benefit of the future city do not often seem to prevail.” Bassett perhaps should not have been surprised, as he was among the first proponents to conceive of zoning as an improved iteration upon the private, term-limited deed restrictions that developers and wealthy homeowners had come to treasure.

The themes of commercialization, citizen objection, and property values—and the role of zoning as a replacement for expiring private deed restrictions—found a chorus in the Murphy Addition upon the introduction of the permanent zoning map and ordinance.

A Map of Morals.

Gerald Gimre, the chief zoning engineer, delivered the comprehensive land use study to the City Planning and Zoning Commission in January 1933. In a memo, he noted that his team had “made a complete survey of all property within the city... setting forth the existing uses of all properties, the character of the buildings thereon and the occupants thereof, the heights of all buildings, the present state of upkeep, the number of families housed in each dwelling, the location of buildings on the lots, [and] the movements of traffic within the city... to assist in arriving at a determination of the character of the various sections of the city. Study maps have also been prepared, showing the existing uses of all properties, the condition of the buildings and the location of the depreciated and blighted properties within the city; also, the location of the negro population, assessed values of properties and the trends of building development during the past few years.”

In the style of the times, racial segregation was made anodyne—a merely scientific and procedural exercise in assumed knowledge. The “negro population” was mapped and categorized as a sort of environmental condition on par with physical blight or the topography of the earth. The “determination of the character of the various sections of the city” upon which zoning classifications would be based was formed not only by the character of buildings, but of their occupants.

The assessment focused little on charting a future for Nashville's development, concerned instead with stemming future intrusion of businesses into fine residential neighborhoods.

Gimre went on to explain:

“Residential neighborhoods will not be invaded by ill-suited uses which so blight the areas surrounding as to cause drastic lowering in the values and character of the neighborhoods and the moral problems which arise from the types of inhabitants which move into such areas. Property values will be sustained and the general good secured by the many benefits accruing to the citizens of Nashville.”

Over the prior half-century, the aforementioned “moral problems” of mixed neighborhoods had become associated almost exclusively with Blackness—transferred to whites only through interracial contacts. White notions of morality were tied to the “types of inhabitants” of mixed-use and mixed-race neighborhoods, and not merely to the actions of individuals.

This context is critical to understand how the construction of a filling station along a major street like West End Avenue could be received as an existential crisis for 276 homeowners across acres of residential neighborhood. The acute problems caused by filling stations and other businesses—traffic, noise, odors—would be felt most immediately by those next-door, and not at all by those further down the block. But the depreciation of next-door homes due to those nuisances would invite lower-class occupants—often Black—who were willing to endure inconveniences to live in an otherwise desirable district, thus setting off a chain of flight and blight which would spread throughout the entire neighborhood.

Zoning was the tool to stop it.

The Zone of Interest.

The majority of the more than 200 citizens who attended the public hearing of the zoning ordinance on July 11, 1933 were homeowners in the Murphy Addition. Homeowners noted that the deed restrictions that had protected their neighborhood from commercial uses—and Black occupancy—were soon to expire and “wanted them perpetuated” by the zoning ordinance.

Their fear was not unfounded—the only two speakers opposed to the bill complained that they had bought property along Charlotte Avenue in the Murphy Addition with the intention of selling it for more profitable commercial use when restrictions expired later that year and would suffer financial harm if the zoning ordinance forbade that option.

Zoning boosters saw the specter of tragic invasion of desirable neighborhoods in a variety of expressions. Automobile ownership grew nearly fourfold in Nashville during the prosperous 1920s and filling stations were most maligned, but concerns were myriad. As the public hearing continued, Murphy Addition homeowners praised ability of the zoning ordinance to negate the blighting effects of chain stores, business houses, and even “half-eaten ice cream cones, thrown away, [which] draw all the flies and when they have dined they visit our homes”—a concern that may seem overwrought today, but which referenced the contemporary association of flies as a vector for the tubercular diseases long associated with Black slums.

The heavy presence of Murphy Addition homeowners and their protests against commercial zoning are illuminated by the context of years of references to the “shifting and changing populations” that created “residential intermixture” and the “moral problems which arise from [certain] types of inhabitants” which follow commercial encroachment.

By the 1930s, the borders of the Murphy Addition had become defined by physical color lines. Charlotte Avenue was the dividing line between their white neighborhood and the Black, working-class neighborhood around Watkins Park. The Murphy Addition was assigned Residence C zoning—the category that allowed apartment buildings, which had been built along State Street and 25th Avenue North—while Watkins Park was designated Residence D, which the Nashville Banner noted “cover those areas which are now inhabited by the Negro population. While the ordinance does not set aside this district as race segregation, the provisions are entirely different from those set up in the other residence districts because of the extreme difference in the character of those sections.”

Another Black residential enclave had followed commercial expansion westward from downtown toward Twentieth Avenue—Murphy Addition homeowners emphasized that exclusion of businesses was especially important “between Twenty-first and Twenty-second avenues” as a buffer to this color line.

With Centennial Park to the west and Vanderbilt University to its south, the Murphy Addition had been backed into a corner by Black residential expansion. If businesses were to invade its borders and blight it with nuisances—and with their racially restrictive covenants no longer in force—a “negro invasion” would likely follow.

Residents of the Murphy Addition protested a handful of commercial classifications along the borders of the neighborhood. Each protest was successful. Protections against commercial encroachment were not afforded to Black neighborhoods like Watkins Park, even though it sat directly across the Charlotte Avenue color line. Around half of Watkins Park was zoned for commercial and industrial uses. The most troublesome predominately Black and racially mixed neighborhoods like Hell’s Half Acre and Black Bottom were zoned for industrial and commercial uses in their entirety, despite their dominant residential makeup—according to Gimre, “in the hope that chance development may improve the character of such districts.”

The purpose of zoning was not to protect neighborhoods from commercial invasions—it was to protect white neighborhoods from commercial invasions, and from the racial invasions which followed.

Decades of public statements from local homeowners and zoning proponents—and half a century of racist associations between Black residence, mixed uses, and blight—were distilled in one public hearing in July 1933 to reveal a more expansive, second-order concern about commercialization than highly localized externalities alone. The white, higher-class residents of the Murphy Addition leveraged immense political capital to protect their property values, with the public police power of a new zoning code to stand in for the private covenants which had maintained exclusivity—social, economic, and racial.

But the color lines that surrounded and defined the Murphy Addition did not hold.

The Murphy Subtraction.

The success of the Murphy Addition as a fine residential district was owed to its location adjacent to both Centennial Park and Vanderbilt University—and to some extent, so was its deterioration as a residential neighborhood. The park and university sat between the Murphy Addition and the white neighborhoods further west and south—without the two institutions as buffer zones, perhaps those neighborhoods would have provided reinforcements to Murphy Addition residents’ fight to maintain residential zoning. Instead, the Murphy Addition residents and their declining political capital were beaten by the forces of progress.

When Nashville was redlined in the late 1930s, the color lines at 21st Avenue North and Charlotte Avenue were maintained. But, walled in by two great anchor institutions and two Black neighborhoods designated “Hazardous” for lending, the Murphy Addition was assigned the next-lowest grade. Lending was restricted to only the most qualified buyers, who saw little advantage to the Murphy Addition relative to the new, Grade A automobile suburbs springing up in Green Hills, Hillwood, and elsewhere in Nashville's unincorporated periphery.

Residential Security (or "redlining") map created by the Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC) in the late 1930s based on input from local lenders, insurers, and planners. This map was later used by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) to inform mortgage insurance qualifications, which effectively restricted loans to areas graded C and D. The Murphy Addition was graded C and largely cut off from federally-backed mortgages in the 1940s. This lack of access to credit contributed to the decline of the district.

Source: Mapping Inequality

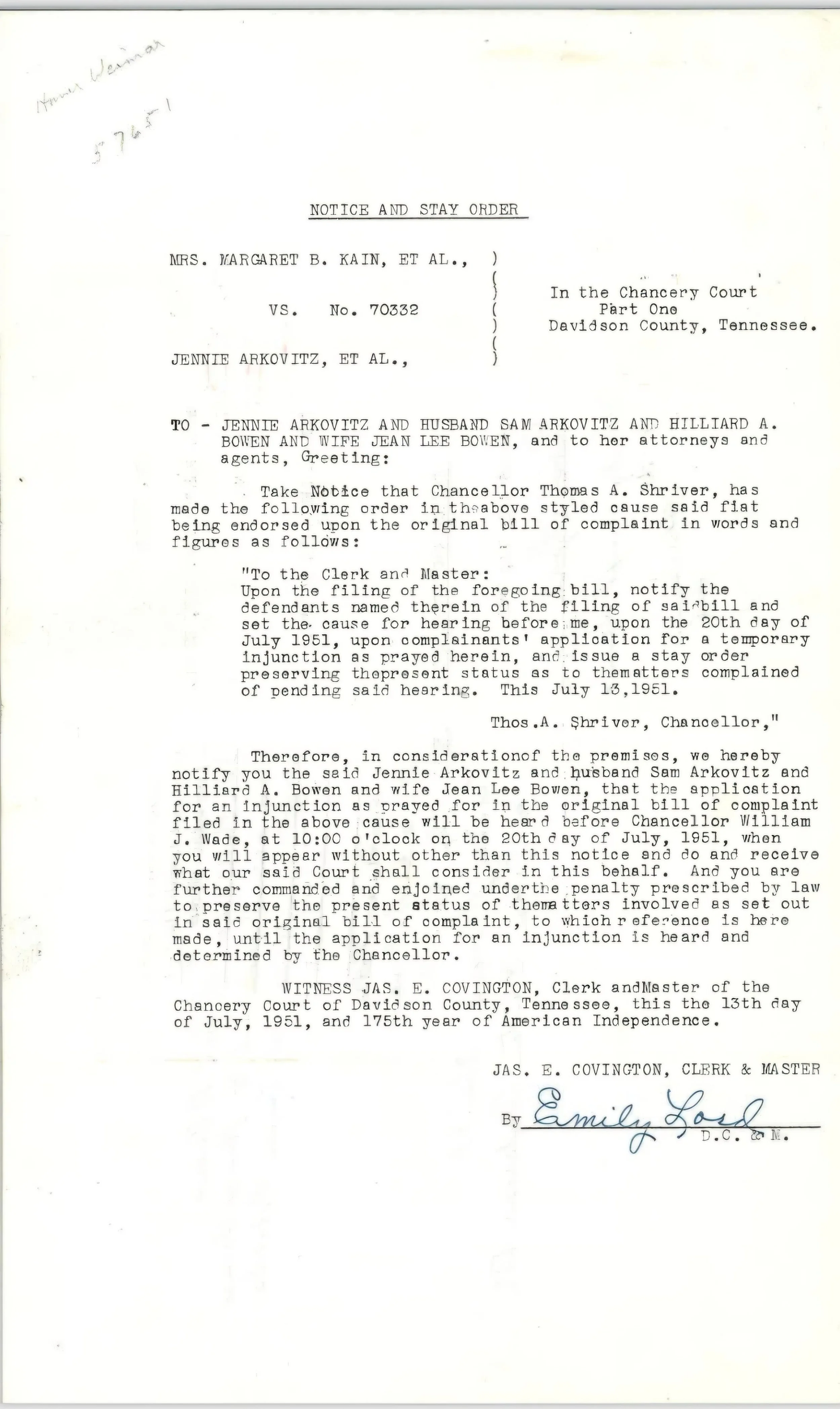

In July 1951, just three years after the U.S. Supreme Court declared racially-restrictive covenants unenforceable in the landmark Shelley v. Kraemer decision, a pair of property owners filed for a temporary injunction to prevent Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Lewis, a Black couple with children, from occupying the house they had purchased at 317 21st Avenue North.

The attorney for Mrs. Margaret B. Kain, of 316 21st Avenue North, and Mrs. Alice Batey, of 318 21st Avenue North, believed it to be the “first legal effort to get around” the Shelley v. Kraemer ruling, as he concocted a legal theory that a set of racial covenants signed by some property owners in the Murphy Addition the year after the 1948 decision should be protected under the “common law of property values.” Kain and Batey were not represented by a crank—the son of a former president of the Nashville Bar Association, R.C. Boyce, Jr. was a respected lawyer and Special Session judge.

“It has been proved that mixed neighborhoods reduce property values and bring about other undesirable factors. This has been a ‘white block’ for years, and the civil rights of the white residents might be affected by Negroes moving in. I believe whites have some civil rights, too.”

With its foundation in the racial theory of property value, the homeowners’ argument echoed nearly half a century of legalistic justifications for segregation—which had, in turn, shaped local zoning regulations and federal housing policy.

A second filing by the white homeowners sought an injunction to eject Dr. Hilliard Bowen—the chairman of the School of Education at Tennessee Agricultural & Industrial State College, now known as Tennessee State University—and his wife, Jean Lee, from the home they had purchased and moved into at 320 21st Avenue North.

Z. Alexander Looby—the iconic civil rights attorney, who won election to the City Council just months before—cited the Kraemer decision in defense of the Bowens: “The State can’t enforce restrictive real estate covenants which deny citizens equal protection due to race.”

But Chancellor Thomas A. Shriver, who served as counsel for the Nashville Housing Authority before presiding as a judge on the Davidson County Chancery Court, granted a temporary injunction against the Lewises after “no one appeared in court for [them].” The white homeowners withdrew the injunction requests against both the Lewises and Bowens on August 2, 1951.

Read the case files: Kain & Batey v. Lewis & Guff and Guff

Read the case files: Kain & Batey v. Lewis & Guff and Guff

Read the Case Files: Kain & Batey v. Arkovitz and Arkovitz & Bowen and Bowen

Read the Case Files: Kain & Batey v. Arkovitz and Arkovitz & Bowen and Bowen

Kain and Batey withdrew the request after the Bowens appeared in court, defended by Looby, and tore apart the covenants—both on technical and constitutional grounds.

The 1949 covenants were crafted to evade the Shelley v. Kraemer decision by expanding the scope from a single transaction to the entire neighborhood. Most covenants were written to bind only the property owner, even when the same covenants were written into the deeds held by every property owner in a subdivision. The post-Kraemer covenants signed by Murphy Addition residents were intended to set the rights of the many signatories in competition with the rights of the parties to the transaction. The Supreme Court had decided it was unconstitutional to enforce covenants placed upon a deed by a prior owner—but what if many other signatories stood to receive damages from a violation?

The theory required great leaps of legal logic—and the plain text of the covenants ensured the mental gymnastics were wasted.

The covenants contained a key clause, which Kain and Batey had withheld from their petition for an injunction: ”This agreement shall not be binding unless signed by all the owners of the property on Twenty-first Avenue, North between Church Street and Murphy Avenue.”

Whether the court would have supported the roundabout legal theory concocted by R.C. Boyce, Jr. is a counterfactual lost to the consequences of that one simple sentence.

Of the twenty-eight homeowners on the 200 and 300 blocks of 21st Avenue North—for decades the frontline of the Murphy Addition color line—all but three signed the racist covenants. Neither the Guffs nor the Arkovitzes were among them. Both had signed on—the act upon which the petition for an injunction was based.

The Guffs noted that “for more than [a] year before the sale… a colored family had resided in this area…” in defense of their sale to the Lewises.

Celeste C. Thompson—the owner of 321 21st Avenue North, the Last Single Family House in the Murphy Addition—was one of the three who refused to sign. She sold the home to Luther and Leona Combs, an elderly Black couple, on August 2nd, 1950—one year before their former neighbors withdrew their attempt to keep the Lewises and Bowens out.

Murphy Addition residents did not restrict themselves to legalistic means to resist integration of the neighborhood. Two days before the Combs family moved into The Last Single-Family House in the Murphy Addition, a cross was burned on its front lawn. Weeks later, a bomb went off half a block away, which Luther Combs believed was “intended to scare him away from the community.” Police investigators shrugged off racial terror as the motive.

Celeste Thompson, like Margaret Kain and Alice Batey, was a dedicated member of the Nashville Catholic Business Women’s League. If Mrs. Thompson had not refused to sign—had she not been willing to defy her neighbors and associates—by selling to the Combses, it is likely that her more racially conservative neighbors may have held the line for many more years. The Guffs and Arkovitzes likely would not have sold, bound in solidarity with their neighbors.

The Last Single-Family House in the Murphy Addition was the first to be sold to a Black family. With the color line broken, many more followed. Margaret Kain and her husband, James, sold their home one year later and moved to the Hillsboro-West End area; she remained civically involved as an election registrar. In 1954, Alice Batey moved from the Murphy Addition to Belmont Boulevard, where she lived until 1966—when the neighborhood was the epicenter of white flight and racial transition in the inner city.

Classified ads for real estate in the Murphy Addition throughout the 1950s would be led with all-capital letters: “COLORED”

But by the 1960s, the classifieds—and the Murphy Addition—would disappear.

The nascent racial transition of the Murphy Addition made it an easy target for sacrifice as the growth of postwar Nashville necessitated expansion of the hospitals which bookended the district. Scattered parcels along Charlotte Avenue had already been converted to commercial use, and a major issue in the 1951 district council campaign was whether to rezone the entire neighborhood to commercial use. Wrenne Phelps, the candidate who campaigned in favor of the rezoning, won election over the incumbent and made good on his promise. In the decades since, the houses the Bowens and Lewises bought—and every other house on the two blocks of 21st Avenue North white homeowners fought to defend—have been torn down, consumed by hospital expansion and secondary development.

Like so many other Nashville neighborhoods, including its neighbor to the north, the identity and residential character of the Murphy Addition were contingent on its status as a white neighborhood.

The Last Single-Family House in the Murphy Addition.

Only one physical remnant of this history remains today. The house at 321 21st Avenue North may stand for many more years, as its intensive zoning translates into a high land value that can only be unlocked by combination with adjoining sites—its redevelopment potential is limited as a narrow, standalone parcel landlocked in the middle of a block.

If a change does happen, it will likely happen soon. James A. Smith bought the house in 1961 with his then-wife, Lovie. When Lovie passed away in 1986, their daughter Gwendolyn was added to the deed, which was then transferred into her name alone in 1989. Gwendolyn passed away on January 18, 2024. Her service was held at Spruce Street Baptist Church, a historically Black church just a few blocks away from the house, on the other side of the old Charlotte Avenue color line.

But for now, the Last Single-Family House in the Murphy Addition stands as a remnant of a much broader history—never wavering from its original use, even as it became home to users it was built to exclude.

Whether it remains this way for many more years or will soon be demolished, the themes it has witnessed continue to be replayed. The Metro zoning code still cites the protection of morals among its purposes. Commercial encroachment continues to be a top target of homeowner activism. Zoning decisions remain deferential to neighborhood protests and neighborhood gatekeepers, with little separation between public powers and private covenants.

These themes survive because every other streetcar suburb prominent in the period of early zoning has survived in its original form, and every other streetcar suburb has survived because these themes are sustained in modern land use and zoning policy.

Only the Murphy Addition is lost to history.

Photo credit: Eric England, The Nashville Scene

This article contains more than one-hundred sources and unearthed events that have never been shared in popular print, based on hundreds of hours of archival research.

If you found it valuable, please consider a show of support.